E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982). Directed by Steven Spielberg, Written by Melissa Mathison. Music by John Williams. Staring Henry Thomas, Drew Barrymore, and Peter Coyote. 115 mins. Rated PG.

Ordinary light, the thing by which those who can see view the world all about. Mostly, all that light (and vision) is just there, pretty much taken for granted, assumed, and thereby depreciated, at least till the lights go out, as in power failure, blindness, or death. We even have the temerity to complain about unsunny days. Woe to us, light and vision just a handy utility, and we think it so all the more because it is so constant and familiar.

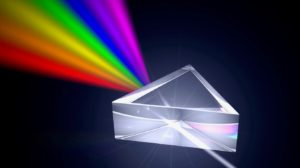

And we know better, sort of. We go to museums and movies (at least occasionally) to see how some others have at times seen light itself, as in Vermeer, Turner, Monet, and Van Gogh, to name the most notable. Most of the time, though, we live in “ordinary light,” rarely taking time to so much as notice light and seeing, let alone to imbibe or relish. However, if we are really, really lucky we come to see light as through a prism. Indeed, look at ordinary light through a prism and suddenly, lo, surprise and wonder, it blooms like a Monet garden or the desert after rain.

With the prism, light itself seems to explode—resplendent in full dazzling spectrum, the source of all color and sight, all heretofore hidden, undetected, and neglected.

Much of the above also applies to the Light, and especially for those accustomed to having it about, as in how many times must one have to listen to bland explications of this or that text. For whatever reasons we all do a pretty good job of killing it off lest it get the better of us. To make sure, in fact, that it does get the better of us, we have, thank God (really), metaphor or, better yet, parable, especially those that unfurl slowly till in surprise and a little awe their real substance flares in such a way as to dazzle just about everyone.

That is certainly the case with Steven Spielberg’s E. T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), a blockbuster that audiences and critics devoured with relish and thanksgiving (Pauline Kael called it a “bliss” of a movie). On the surface, the sci-fi tale is simple enough: an ungainly, and very frightened, alien is marooned on a physically and socially unfriendly earth until eventual retrieval by his peers. No big deal, hardly the occasion, it seems, for gush or parable. What this tale is, though, bluntly put, is a rather perfect retelling of the Jesus story, the whole outlandish shebang, and in that, unbeknownst to all those secular hordes, and Christians too, who adored the film, lay its power (for specific detail, see entries on resurrection and ascension in ET). The film’s screenwriter, the late Melissa Mathison, Catholic schoolgirl that she was, realized halfway through shooting that she had delivered, unbeknownst to her own self, a full-blown, and lush, Jesus story. That she surely did.

Consider: a resounding tale limning what it feels like when God shows up incognito among a weary, bedraggled humanity. And this film/parable does make Christian folks wonder if they’d do any better recognizing God than they did the first time—or how wrong they might now be, thinking that they maybe have already all figured out this God thing, all poked and probed and dogmatized, just like science. The virtues of films like E.T. is that they show how much we folks don’t know about what God looks like and where and how God shows up. Indeed, if we’re lucky, amid those necessary, searching tears of sorrow and gladness we may get just a glimpse, even though it’s refracted through a kid’s tale of a lost alien. Surprise.

E.T. essentially repeats the narrative arc that is at the heart of the Good News. From obscurity and ignobility, at least geographic and ethnic, comes Jesus. Add to that the notion that he was not much to look at, very far from the handsome conquering hero on a white horse, we have something decidedly lowly, at least from usual human standards (Isaiah).

From that circumstance comes the unlikely prophet who cares for others, for those much like himself, the forsaken and lowly, those without help or succor, the widows, orphans, prisoners, and aliens, meaning strangers (Matthew 25, as well as the Sermon on the Mount, the most remarkable poem ever preached). This is not a formula to win favor with the fancy, vain, and powerful. So different is this loving others, really caring, that it will likely get you killed, a strategy that promises to return you to wherever you came from or wherever.

So in E.T. there is the human protagonist Elliott, himself one of the lowly and outcast. After all, his father has run off with the secretary, leaving Elliott with a younger sister, an older brother, and one hapless mother. And then Elliott happens to find a literal alien, equally deserted, abandoned by his peers in a close escape. Slowly all discover that this funny looking creature, looking so helpless and forlorn, is—surprise, surprise–super-natural, or at least far beyond earthly natural. Telekinesis he has, which is pretty impressive, but it pales next to what he can do with that glowing finger, healing cut fingers and resurrecting dead flowers. Perhaps the starkest visual giveaway is ET’s glowing red heart, an effect borrowed from much traditional devotional art depicting the Virgin Mary and her depthless compassion. Indeed, this increasingly marvelous creature—both wondrous and most gentle–shocks not only in his unexpected arrival and bizarre appearance but more so in the powers he wields—and the ends toward which he wields them, especially in contrast to the harsh world of the adults, and, among them, the scientists, themselves trying to control the natural, a generally cruel and heartless lot who see in the dying ET a splendid research opportunity.

What the scientists could never do for ET, Elliott does–and ET for Elliott–and that is the most vital stuff in the world, the whole of it, on earth and, apparently, far beyond, whether planetary or heavenly. The thing that makes all these worlds go round, no matter how different and far flung, is love, and in E.T. that love gets theologized, made into Love with a capital “L,” in very big ways. To put the matter simply, and without the symbol-mongering in which many critics indulge, ET the character is a rather fully-blown, and very richly drawn, Christ-figure. Parable strikes again–once upon a time, a small lonely creature was found, whether as boy or alien—and it is not only illuminating but deeply affecting, as in delight, elation, awe, and tears for who knows what. And so we should respond as those in E.T., a film that tutors on how to see and feel, as at last Eliott’s mother does as she watches in wonder and elation as ET’s ship begins its ascent.

And, yes, alien and Christ alike, each is revolutionary, personally and socially. From ET’s mysterious arrival to his healing powers to his resurrection (by Love, from Elliott and his fellow aliens who are coming to fetch him), aerial escape (walking on water), and ascension (there on the mountaintop and in his farewell words), the story tracks the arc and core of the biblical story.

That all of this is something that most don’t see clearly, perhaps especially churchgoers, mostly because they’re too busy and/or blind to see and, in this current techno culture, too deluded and bedazzled by all those gadgets. The doors of perception are hard to open, perhaps harder than ever, though we sometimes find the key in the darnedest places. Once having seen, all has come clear and radiant for young Elliott, confessing that “I’ll believe in you all my life, everyday. ET, I love you.” And light is where the film ends, boy and creature, bathed in light, hanging on for a dearer life, as Annie Dillard once put it (“Living Like Weasels”).

written by Roy Anker

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Insights on preaching and sermon ideas, straight to your inbox. Delivered Weekly!

Categorized into Incarnation

E.T. the Extra Terrestrial (1982) – 2